Near misses and tragic losses – sailing the last commercial wind ships

Built to carry bulk cargo across oceans, windjammers were able to weather all but the most ferocious of storms. The enormous iron and steel ships reveled in strong winds, carrying them to their destination all the faster. Windjammers were not immune to the perils of the seas – age, design flaws and sometimes mistakes made under pressure in treacherous conditions, would lead to disaster.

In 1932, Hougomont was dismasted in a storm 950 kilometres south of Cape Borda, South Australia. A passing steam ship telegraphed to Adelaide and alerted the authorities to the ships distress. Captain Ragnar Lindholm, and his crew had set to work removing the enormous masts and building a makeshift rig and by the time the tug Wato reached them they were sailing slowly toward Port Adelaide. Captain Lindhom refused the offer of a tow because he did not want to pay salvage fees. No doubt, his thriftiness was appreciated by his employer Gustaf Erikson who was renowned for saving money wherever he could. After 19 days of slow sailing, they reached the anchorage at Semaphore. The ship was stripped of any useful fitting and the hull was towed to Stenhouse Bay where it was scuttled as a breakwater. The wheel from the helm is on display in the SA Maritime Museum and the figurehead, a lady dressed in a white gown, is displayed in Åland Maritime Museum in Mariehamn.

The sailors on board the Dutch sail training ship the København, were not so lucky. Known as the “Big Dane”, it was the largest sailing ship in the world when launched in 1921 and was used to train cadet sailors. The five-masted barque made several successful voyages including two circumnavigations. In 1926, the crew and young cadets visited Port Germein touring nearby farms and welcoming locals on board the ship. Tragically, two years later all 75 crew were lost in the Southern Atlantic without a trace. For several years afterwards, there were sightings of a mysterious five-masted ship and fragments of evidence including a piece of stern board bearing the name København slowly came to light. It was thought the ship had either struck an iceberg in the night or perhaps, capsized in a storm rendering lifeboats useless.

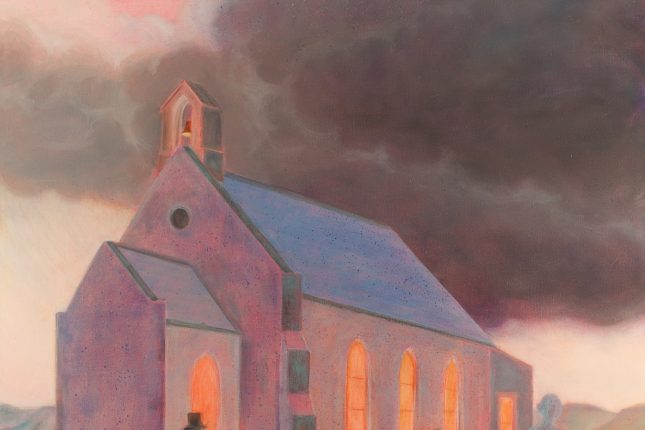

A ship of great renown Herzogin Cecilie also met a disastrous fate although tragedy was averted. ‘The Duchess’, as the ship was known, was one of the fastest windjammers ever built, logging 21 knots at Skagen, Denmark. It was the pride of the Erikson fleet, winning the Great Grain Race from South Australia to Europe more than any other ship. The final passage of 86 days was the second-fastest ever. The crew celebrated after reaching Falmouth and the young captain Sven Eriksson, fatefully chose to sail for Ipswich, through the foggy night. The Duchess ran aground on Ham Stone Rock, Devon. Pamela Eriksson, who had sailed with her new husband, spearheaded a fundraising campaign to save the ship, although ultimately it was never salvaged.

Herzogin Cecilie at what would become its final resting place

Show all

Show all

Read this post

Read this post

Visit

Visit